In seminar yesterday we were discussing the following argument, which purports to be an a priori argument that if most Xs are Ys, then all Xs are Ys. (This is a slightly simplified version of the argument in “Induction and Supposition”:http://brian.weatherson.org/IaS.pdf, but I think the simplifications are irrelevant to what I’m saying here.)

- Assume most Xs are Ys, for conditional proof.

- Assume a is an X.

- Then a is a Y. (By statistical syllogism.)

- So if a is an X, then a is a Y. (By conditional proof, discharging assumption 2.)

- So for all x, if x is an X, then x is a Y. I.e., all Xs are Ys. (By universal introduction, since ‘a’ was arbitrary.)

- So if most Xs are Ys, then all Xs are Ys. (By conditional proof, discharging assumption 1.)

The conclusion is absurd, so the issue is which is the mistaken step. My conclusion is that the mistake is to apply ampliative inference rules, like statistical syllogism, inside the scope of a supposition. Indeed, I think the core mistake is to think that we can formalise inference rules as being things that can slot into natural deduction proofs. Proofs are things that tell you about implication, and inference rules are things that tell you about good inference, and implication is not, after all, inference.

But the conclusion of the last paragraph would be better supported if I could claim there is nothing else wrong with the proof, save for the use of an inference rule at a point in the proof where only a rule of implication is permitted. And that was being disputed.

We know that statistical syllogism has defeaters. It isn’t good to infer that a is Y from Most Xs are Ys and a is X, if you have strong independent evidence that a is not Y. I wanted to reason as follows. The inference from Most Xs are Ys and a is X to a is Y goes through in the absence of any reason to think that a is especially likely to be not Y. You don’t need to have a positive reason to think that a is a ‘normal’ X (with respect to Y-hood). You just need an absence of reason to think it is abnormal. And of course you have an absence of such a reason. We’re doing this all a priori, and we don’t know anything about a. So the conditions for using statistical syllogism in *inference* are met.

The reply that my students came up with was two-fold. (I think the reply was primarily due to Una Stojnic, Lisa Miracchi and Tom Donaldson, though there was a fairly wide ranging discussion.) First, if ‘a’ is a dummy name, or as it were the name of an arbitrary object, then we can’t really say that this condition is satisfied. We know that it’s not true that the arbitrary object is not normal. After all, some Xs are not Ys. Or, at least, we have no reason to think they all are. So we must be treating ‘a’ as the name of a real object, not a ‘dummy name’, or the name of an ‘arbitrary object’. But there’s an issue about which kinds of objects we can even refer to in a priori reasoning. Perhaps the only objects we can refer to a priori are abstract mathematical objects (like the null set, or the number 2). And the problem then is that we may well have reason to defeat the statistical inference from 1 and 2 to 3, since a priori we may know that a is a special case. For instance, the following reasoning is bad a priori.

- Assume most primes are odd.

- Assume two is prime.

- So two is odd. (By statistical syllogism.)

- So if two is prime, two is odd.

- Since two is arbitrary, all primes are odd.

- So if most primes are odd, all primes are odd.

That’s bad reasoning because (perhaps inter alia) it’s a bad use of statistical syllogism. And it’s a bad use of statistical syllogism because even a priori we have reason to think that two is an ‘abnormal’ prime with respect to parity.

So there’s a dilemma for the reasoning I was using. If ‘a’ is a genuinely referring expression, then it isn’t clear that the preconditions for statistical syllogism are satisfied, because the only things it could refer to in a priori reasoning are things that we have a priori knowledge about. But if ‘a’ isn’t a referring expression, then it seems surely true that the step from 1 and 2 to 3 fails. Either way, we have reason to think the argument to 3 is bad, and that reason is independent of my general view that you can’t use ampliative inference rules (if such things exist) in suppositional reasoning.

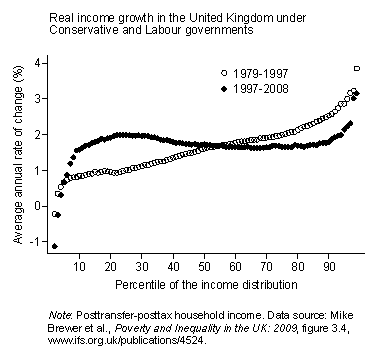

“Matt Yglesias”:http://yglesias.thinkprogress.org/2010/09/new-labour-and-inequality/ and “Brad DeLong”:http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2010/09/in-which-matthew-yglesias-observes-that-innumeracy-is-an-awful-thing.html have argued that this graph, from “Lane Kenworthy”:http://lanekenworthy.net/2009/06/01/did-blair-and-brown-fail-on-inequality/, shows that we shouldn’t be too critical of Labour’s performance with respect to inequality over their 12 years of government in Britain.

“Matt Yglesias”:http://yglesias.thinkprogress.org/2010/09/new-labour-and-inequality/ and “Brad DeLong”:http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2010/09/in-which-matthew-yglesias-observes-that-innumeracy-is-an-awful-thing.html have argued that this graph, from “Lane Kenworthy”:http://lanekenworthy.net/2009/06/01/did-blair-and-brown-fail-on-inequality/, shows that we shouldn’t be too critical of Labour’s performance with respect to inequality over their 12 years of government in Britain.